Purple Sea Star

Pisaster ochraceus

The purple sea star was one of the first keystone species identified by scientists. It is a top predator that keeps the number of species in tide pools relatively stable.

In the mid-1900s, ecologists wanted to understand what controls the population sizes of organisms. Ecologist Fred Smith approached this problem by asking a related question: “What keeps the world green?” In other words, what keeps all the plants from being eaten by herbivores?.

Fred Smith’s green world hypothesis

Smith and his colleagues proposed that predators play a key role in maintaining the numbers of plants in an ecosystem — mainly by limiting the number of herbivores. To test this idea, which became known as the green world hypothesis, ecologist Robert Paine looked for an ecosystem in which he could observe the effects of a predator on the rest of the community. He chose tide pools because they have clear physical boundaries and relatively simple food webs.

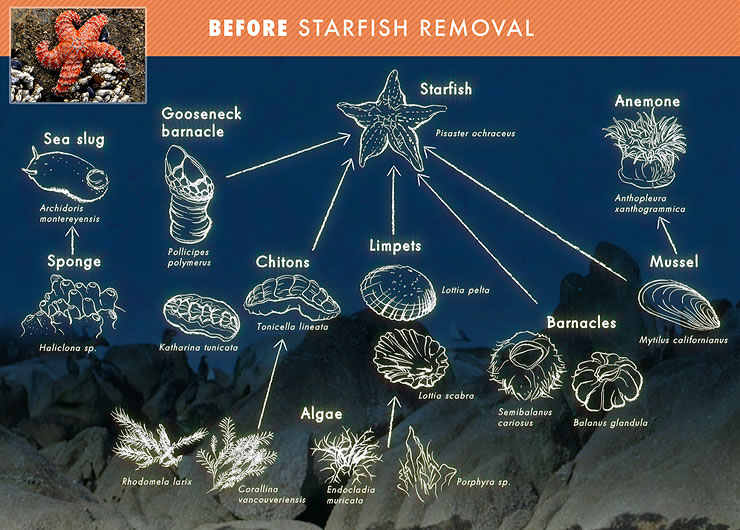

Paine removed the top predator, the purple sea star, from several North Pacific tide pools. Then, he observed changes to the remaining plants and animals in the ecosystem

Purple sea star (Pisaster ochraceus)

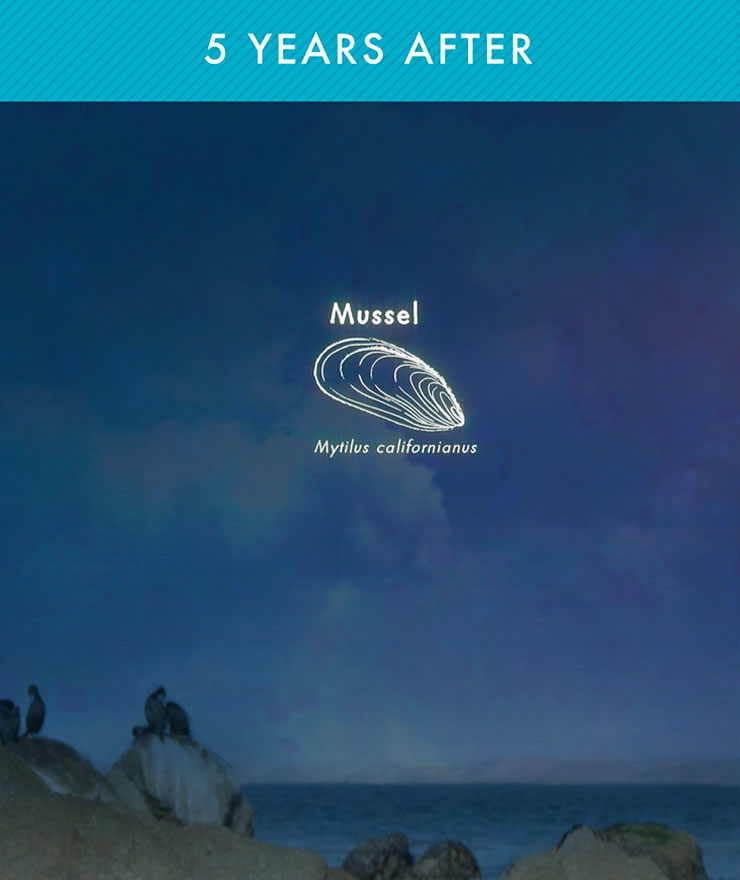

At the beginning of Paine’s experiment, the ecosystem had 16 species. One year later, it was down to eight species. After five years, only one species remained: a type of mussel that was usually preyed on by the purple sea star. The absence of the sea star had allowed the mussel to take over, collapsing the diversity of the ecosystem to a single species.

A tide pool at low tide showing diverse organisms, including sea anemones and algae Photo credit: iStock/Getty Images Plus

Mussels, one of the species preyed on by purple sea stars Photo credit: iStock/Getty Images Plus

A tide pool without purple sea stars, now dominated by mussels Photo credit: iStock/Getty Images Plus

A food web showing the 16 species in the tide pools at the start of Paine’s experiment

A food web of the species one year after removing the purple sea star

The only species remaining five years after removing the purple sea star

Paine tried experiments in which he removed species other than the purple sea star from tide pools. However, the absence of other species did not have such a dramatic impact. In 1969, Paine came up with the concept of a “keystone species” to describe the sea star’s unusually large effects. His work inspired decades of research into how the presence or absence of certain species affects ecosystems.