Sea Otter

Enhydra lutris

Sea otters in the Northern Pacific are important to the health of kelp forests. They keep herbivores like sea urchins in check and the ecosystem in balance.

Range map of the sea otter

In the past, sea otters numbered in the hundreds of thousands and lived over a large range: from southern California up the coast to Alaska, across to the Kamchatka Peninsula, and down to Japan.

Sea otter (Enhydra lutris)

But in the 1700s and 1800s, otters were hunted almost to extinction for their fur. When hunting was finally restricted, otter populations returned to some places but not others. The presence and absence of otters in different locations allowed ecologist Jim Estes to investigate the role of otters in their ecosystems. He focused on kelp forests in the Northern Pacific Ocean, underwater ecosystems that contain many large seaweeds called kelp.

In the kelp forests, otters are the main predator of sea urchins. Estes found that where otters were present, they kept sea urchin numbers in check, preventing the urchins from eating all the kelp. The kelp forests with otters were healthy, providing habitat for thousands of species of fish, seabirds, and invertebrates.

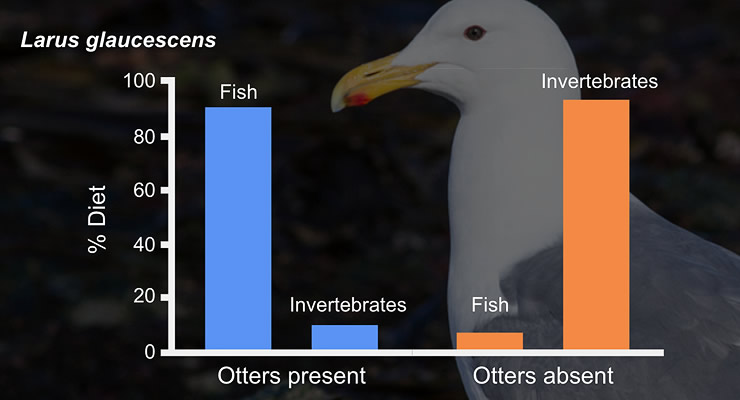

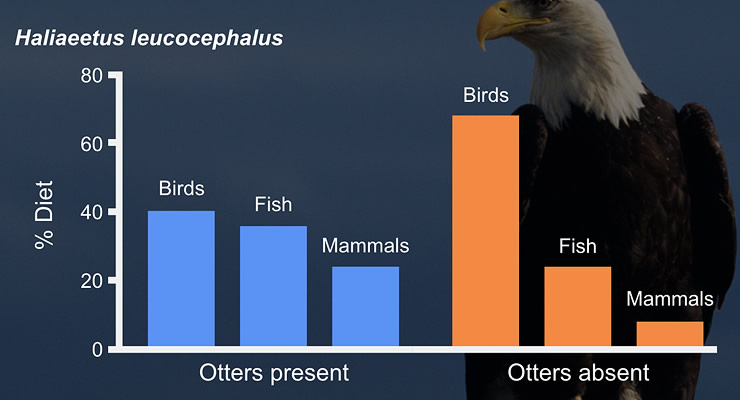

Where otters were absent, the number of sea urchins exploded. The urchins ate much of the kelp, impacting species that rely on the kelp forest ecosystem. The diets of birds that feed on kelp forest species, for example, changed significantly in the absence of otters. Scientists call this type of ripple effect a trophic cascade. In this trophic cascade, a change in one species, the sea otter, indirectly affected many other species in the ecosystem.