Virus Explorer

Click and drag or use the buttons below to move the model.

Use the tab to focus one of the buttons above, and

then space to start the rotation.

The viral envelope (gray) and proteins embedded in the envelope (red) are shown.

Components on the virus are selectively represented in the 3D model for educational purposes.

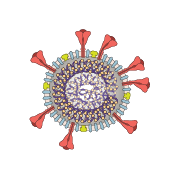

A. RNA genome; B. Nucleoprotein; C. Lipid envelope; D. Envelope protein; E. Membrane protein; F. Glycoprotein

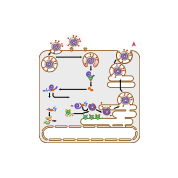

This diagram shows how coronaviruses replicate, or make copies of themselves. Glycoproteins on the surface of coronavirus bind to specific receptors on the host cell’s surface (A), which allows the virus to enter the cell. Some coronaviruses enter by fusing their envelope directly with the cell membrane on the it’s surface. Other coronaviruses trigger a process known as endocytosis, shown here (B), which brings the virus into the cell in a structure called an endosome. Acidic substances build up inside the endosome, lowering the pH and triggering the endosome’s membrane to fuse with the virus’s envelope, releasing the virus’s (+)RNA genome into the cell’s cytosol (C).

Ribosomes in the cytosol translate the virus’s (+)RNA genome into a viral polymerase protein (D). The polymerase transcribes the virus’s genome into a complementary, (–)RNA template (E). This template is used to make copies of the virus’s whole (+)RNA genome (F) and to transcribe mRNAs (G). The mRNAs are translated into proteins by ribosomes in the cytosol and on endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (H).

Viral genomes and proteins are assembled into new viruses in the ER-Golgi netowork, where the viral proteins are further modified through protein processing (I), and also go through a process called budding. This process surrounds the virus in a piece of the cell membrane containing viral proteins, which becomes the virus’s envelope. Once a new virus becomes fully formed through a series of changes called virus maturation (J), it is released from the cell in a process known as exocytosis (K).

Coronavirus

- Coronaviridae family

- ~100-nm enveloped particles with a helical capsid

- Linear (+)ssRNA genome of ~30,000 bp

- Infects birds and humans and other mammals

- Vaccines are available against one type of coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2

Coronaviruses are a family of viruses with many members. Diseases caused by coronaviruses are often respiratory in humans and gastrointestinal in other animals.

Although less than 10 species of coronaviruses are known to cause disease in humans, they have caused several major outbreaks — including a 2002 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which was caused by a coronavirus called SARS-CoV-1, and a 2012 outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), which was caused by a coronavirus called MERS-CoV. Both outbreaks were caused by transmission from infected animals (such as bats, civets, or camels) to humans, making these coronaviruses zoonotic viruses.

In early 2020, a new coronavirus, called SARS-CoV-2, began to infect people across the globe. SARS-CoV-2 spread easily among humans who lacked immunity to the virus. This coronavirus causes a disease called COVID-19. COVID-19 initially overwhelmed hospitals in many countries and caused many deaths. The first vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 became available in 2021. These vaccines protect against severe illness, hospitalization, and death from COVID-19.