Main Content

From the President

Robert Tjian, HHMI president. Credit: James Kegley.

In the United States, perhaps more so than anywhere else in the world, we enjoy a rich tradition of philanthropy. This tradition propels scientific discovery, economic growth, and social gains. In many cases, philanthropy complements the work that governments and companies undertake. As I look back on 2015, I’m struck by how important individual and organizational philanthropists have become for the future of science and society.

A hallmark of philanthropy is a willingness to take risks and to provide the longer runway that projects often need to succeed. For basic research, or what some call “discovery science,” this mindset is critical. Such fundamental research is widely considered a high-risk exploration for transformational discoveries that often have no obvious immediate application but can hold the key to high-impact advances.

Despite a well-documented history of successes driven by such foundational research in the life sciences, today there is little room for basic science in pharmaceutical companies, which can spend $1–2 billion to produce a single drug. Similarly, government agencies feel mounting pressure to generate immediate returns with taxpayer dollars and thus to favor translational and applied research. In this scenario, there is an opening for others to step in and fund the high-risk, high-reward basic research that can yield truly seismic discoveries and inventions.

Since 2009, it has been my privilege to lead HHMI and to help drive science forward. We’ve found the best success when we focus on supporting people, rather than projects. We look for scientists who are exceptionally creative, persistent, and technically sound, and then give them the resources to pursue their dreams and develop the ideas they’re passionate about. We evaluate them rigorously and hold them accountable for original thinking and stellar science.

These efforts – combined with our ambitious work in science education to strengthen the caliber and number of scientists entering the pipeline – have yielded significant returns for HHMI and for science globally. I’ve found this work personally to be challenging, interesting, and exciting, and that’s why it’s bittersweet that 2016 is my last year as HHMI president. Like other investigators, I find it natural to constantly explore and shift directions. I plan to return to my lab at the University of California, Berkeley, and continue to pursue my interests in advancing the field of gene regulation. There is still much for me, and for HHMI, to do.

Thank you.

Robert Tjian

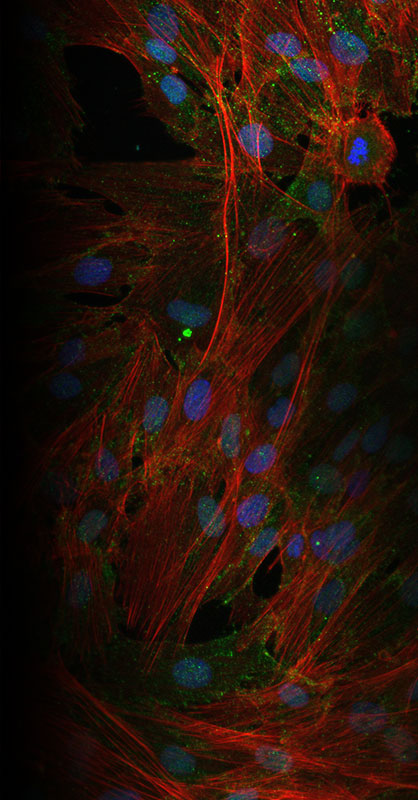

Fibroblasts are the most abundant cells in animal connective tissue. These human fibroblasts have been stained to reveal their cytoskeleton (red), mitochondria (green), and DNA (blue).

Jaclyn Ho, University of California, Berkeley.