2014 Year in Review

2014 Highlights

Nobel Lights Up Lab

Janelia Group Leader Eric Betzig shared the 2014 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Stefan Hell of the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry and William Moerner of Stanford University. The Nobel Committee honored the three scientists for their development of super-resolved fluorescence microscopy – methods of visualizing objects so small that, until recently, distinguishing them with a light microscope was considered a feat that would defy the fundamental laws of physics.

Learn more about the Nobel-winning work ›Clipping DNA Damage

When a strand of DNA breaks in a yeast cell, a protein called Sae2 is one of the first to come to the rescue. The molecule sweeps in and trims the damaged ends of the DNA in preparation for repair. But if Sae2 lingers too long, it runs the risk of clipping some perfectly good DNA as well. HHMI Investigator Tanya Paull’s team discovered that cells prevent this from happening by storing Sae2 in nonfunctional, insoluble aggregates. Once DNA damage occurs, the aggregates break apart, freeing Sae2 to do its job.

Read more about Paull’s work in the HHMI Bulletin ›New Advanced Imaging Center

Even leading scientists must often wait years to try out new technologies for probing biological systems. To accelerate science, HHMI has partnered with the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation to create an Advanced Imaging Center that shares optical imaging microscopes developed at Janelia. The Center invites select scientists, chosen through open competitions, to use the microscopes at no cost with expert assistance before the instruments become commercially available.

Learn more about the Advanced Imaging Center ›Moved By A Memory

Everyday experiences become intimately associated with emotion as they are stored in the brain. Contextual information about these events – where and when they happened – is recorded in the brain’s hippocampus, while the emotional component of the memory is stored separately, in the amygdala. Working in mice, HHMI Investigator Susumu Tonegawa and colleagues showed that the circuit connecting the two can be rewired, giving the memory of an event a new emotional association. This connecting circuit could provide a new target for drug developers to treat mental illness.

Read more about Tonegawa’s findings ›Meet 15 HHMI Professors

In June, HHMI named 15 leading scientist-educators as HHMI professors. Each will receive $1 million over five years to create activities that integrate their research with student learning. Much of the responsibility for sustaining excellence in science falls on the nation’s research universities, home to some of the world’s best scientists and attended by some of the nation’s most talented students. The newly selected professors – who represent 13 universities across the country – will join the community of HHMI professors who are working together to change undergraduate science education in the United States.

Learn about the professors in the HHMI Bulletin ›Turning Off Tumor Cells

Glioblastomas are some of the most common – and most lethal – brain tumors. Their deadliness arises, in part, from a small population of stem cells that drives tumor growth and provides resistance to treatment. Early Career Scientist Bradley Bernstein and HHMI Investigator Aviv Regev teamed up to look for a way to disarm these cells. They discovered four transcription factors – proteins that turn genes on and off – that are present only in the tumor’s stem cells. Targeting these unique proteins may provide a way to defeat the deadly tumors.

Learn more about the scientists’ work in the HHMI Bulletin ›Jump! An Evolutionary Arms Race

For millions of years, bits of DNA called retrotransposons have been duplicating and inserting themselves randomly into the genomes of different organisms, including humans. Fortunately, as a team led by HHMI Investigator David Haussler showed, cells have evolved a way to keep these wayward sequences in check. A family of more than 400 rapidly evolving genes produces proteins called KRAB zinc-fingers that scan the genome, clamp on to retrotransposons, and then call on other molecules to silence them. To evade detection, retrotransposons will mutate, which drives the evolution of new KRAB zinc-fingers and keeps the pair locked in an evolutionary arms race.

Read more about Haussler’s work ›Science, On Screen Near You

Storytelling is one of the most powerful tools in science. A compelling film can profoundly impact how people think, by asking hard questions or sharing the thrill of discovery. In 2014, HHMI’s growing media initiative took viewers inside evolution, the need for vaccines, and the potential for a sixth mass extinction, among other issues. From high school classrooms to the big screen, our stories touched millions of viewers.

Learn more about Tangled Bank Studios › Watch all of HHMI's short films ›How Big Is This Place?

Information about people, places, and events is stored in the brain’s hippocampus. By allowing rats to incrementally explore a large maze, Janelia Group Leader Albert Lee and his team figured out how this small region ensures that it has enough storage space for larger and longer experiences. Populations of nerve cells in the hippocampus are divided: certain cells are ready to represent smaller areas; others are ready to represent medium-size areas; and still others, large areas. Similar mechanisms are most likely at work when the human brain records a new experience.

Read more about Lee’s work ›Expanding Access To STEM

Good science requires fresh ideas and a broad talent pool, and diversity is a foundation for both. For 25 years, the Meyerhoff Scholars Program at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), has been steadily boosting the number of underrepresented groups in the upper ranks of math and science. HHMI is partnering with UMBC to adapt the Meyerhoff model to two other schools, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Pennsylvania State University. The partners plan to document, assess, and share information about what they learn so that other universities might follow.

Learn more about the Meyerhoff Adaptation Project ›Decisions, Decisions

We’re hardwired to learn from our mistakes, but sometimes it’s better to abandon lessons learned and act less strategically. The way the brain switches between paying attention to past experiences and proceeding randomly is clearer now, thanks to new findings from the lab of Janelia Group Leader Alla Karpova. Her team was able to suppress a rat’s strategic mode and trigger random behavior by increasing levels of a stress hormone called norepinephrine in the brain’s anterior cingulate cortex. Inhibiting release of the hormone had the opposite effect. Karpova suspects that the same neural mechanisms govern the way humans act.

Read more about Karpova’s work ›Awards and Honors

Walter Wins Pair of Prizes

HHMI Investigator Peter Walter of the University of California, San Francisco, and Kazutoshi Mori of Kyoto University shared both the 2014 Albert Lasker Basic Medical Research Award and the 2014 Shaw Prize in Life Science and Medicine. The scientists were honored for their discoveries detailing a complex quality control process – the so-called unfolded protein response – of the endoplasmic reticulum, a labyrinth of cellular membranes where proteins are folded and groomed before being shipped to precise destinations to carry out their functions. The process is so crucial to cells that imbalances can lead to a number of diseases, including cancer, diabetes, cystic fibrosis, and vascular and neurodegenerative diseases.

Read more about Walter’s Lasker Award › Read more about Walter’s Shaw Prize ›Breakthrough Prize for Genome Editing Technology

HHMI Investigator Jennifer A. Doudna of the University of California, Berkeley, was among six scientists awarded the Breakthrough Prize in Life Sciences. Doudna was honored along with Emmanuelle Charpentier of the Helmholtz Center for Infection Research and Umeå University for turning an ancient mechanism of bacterial immunity into a powerful technology for editing genomes. The mechanism, called CRISPR, uses small pieces of RNA to recognize and destroy invading viruses and plasmids. Doudna’s team adapted the system so that it could be guided by a customizable RNA molecule, giving scientists the ability to cleave DNA at precise locations.

Learn more about Doudna’s prize-winning work ›Films Win Multiple Awards

From short films to full-length documentaries, HHMI science education media garnered international recognition in 2014, including awards from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, CINE, the Wildscreen Film Festival, and the Jackson Hole Wildlife Film Festival, among others. The awards reflect the diverse audiences for our BioInteractive and Tangled Bank Studios media, from students and educators to the public at large.

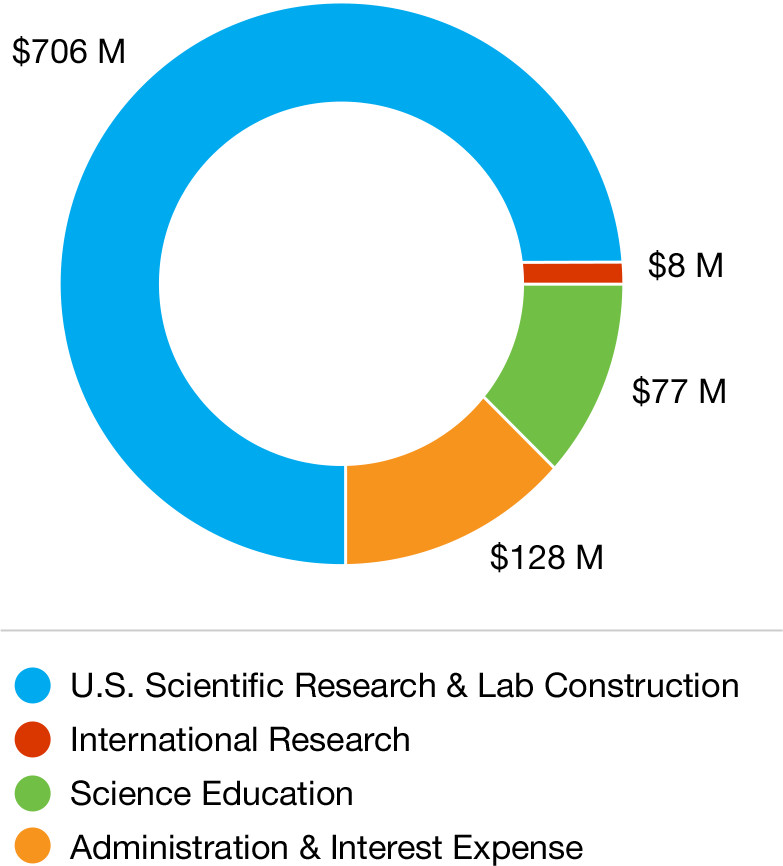

Learn more about Tangled Bank Studios › Watch all of HHMI's short films ›Financials An overview of HHMI’s endowment and disbursements in 2014

The Howard Hughes Medical Institute is the nation’s largest private supporter of academic biomedical research. As a medical research organization, the Institute spends at least 3.5 percent of its endowment each year on research activities and related overhead, excluding grants and investment management expenses. At the close of fiscal year 2014, the Institute had $18.6 billion in diversified net assets – an increase of $1.7 billion from the previous fiscal year’s end. Since 2005, the Institute has provided almost $8 billion in direct support for research and science education. View HHMI’s full financials » Download this report as a PDF » Can’t open PDF files? Download Adobe Reader »